|

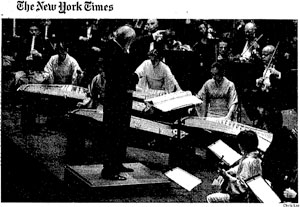

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakovwrote the book on orchestration •. but along· side the Japanese composer Minoru Miki In 'the New York Philharmonic concert at Avery Fisher Hall on Thursday evening, Rimsky seemed a piker. Kurt Masur led the orches-tra In Mr. Miki's "Symphony for Two Worlds," which combines a full Western orchestra with a 16·mem-bel' band playing Japanese instruments: here, Pro Musica Nipponia, founded by Mr. Mikin 1964. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakovwrote the book on orchestration •. but along· side the Japanese composer Minoru Miki In 'the New York Philharmonic concert at Avery Fisher Hall on Thursday evening, Rimsky seemed a piker. Kurt Masur led the orches-tra In Mr. Miki's "Symphony for Two Worlds," which combines a full Western orchestra with a 16·mem-bel' band playing Japanese instruments: here, Pro Musica Nipponia, founded by Mr. Mikin 1964.

In this symphony, which was commissioned by Mr. Masur's other orchestra, the Leipzig Gewandhaus, for its 200th anniversary In 1981, Mr. Miki seeks to build bridges but works squarely within the Western symphonic tradition. Although the Japanese Instruments, few and mostly ancient, stand up to the larger, sleeker· ensemble remarkably well in Mr. Miki's exquisitely gauged scoring, in the end they add little more than color.

But they add lots of it, and Mr. Miki exploits it cannily. Some combinations are obvious (long lines on hoarse, recorderlike, shakuhachis against sweet warblings on Western flutes), others less so. The juxtaposition of delicate, plucked kotos with brasses is strikingly original despite Prokofiev's zany mandolin-trumpet precedent in "Romeo and Juliet," Virtually every Instrument, Japanese and Western, gains prominence at some point or other, but the piece is most delightful when the whole elaborate contraption chugs along al once, sending sparks In every direction. Mr. Miki's deft transformation of Eastern- and Western-sounding themes Insures overall unity. Although Rimsky·Korsakov's "Scheherazade" has never really dropped from sight, It has mercifully seemed less than ubiquitous over the last decade, and It Is almost possible to hear the work with fresh ears, al least In a fresh performance like Mr. Masur's. As David Wright aptly observes In the program notes, the work's sinuous orientalisms afforded early audiences "an encounter with the unknown," as Mr. Miki's cultural cross·fertilization does now.

Mr. Masur, perhaps identifying more with the gruff sultan of Rimsky's program than with the tale-spinning Scheherazade, avoided the typical saccharine approach to this music, giving full vent to its dynamism. Glenn Dicterow, the concertmaster, played the extensive violin solos beautifully, and the wood· wind principals were fine in their solos, especially Judith LeClair, the bassoonist and chief beneficiary of Rimsky's Imaginative scoring.

Some string chatterings were blurred, and a few tempo shifts seemed unsettled. What's more, it became clear In several piano and pianissimo passages that even three years Into the Masur era, quiet play· ing does not come naturally to this orchestra and must to some extent be imposed.

Mr. Miki presided over a brief preconcert demonstration of the Japanese instruments by members of Pro Musica. As useful as the snippets were, a listener could not help wishing for a more complete musical statement from one or several of these superbly skilled performers. Junko Tahara, In particular, played the biwa (a lute with a sitarlike sonority) while intoning a compelling medieval selection that should have gone on longer.

The "Symphony for Two Worlds” is to form the basis for a Philharmonic Young People's Concert Hall afternoon at Avery Fisher Hall, and the entire program will be repeated this evening. Pro Musica Nlpponla is to perform more of Mr. Miki's music tomorrow at the Miller Theater or the campus of Columbia University.

|

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakovwrote the book on orchestration •. but along· side the Japanese composer Minoru Miki In 'the New York Philharmonic concert at Avery Fisher Hall on Thursday evening, Rimsky seemed a piker. Kurt Masur led the orches-tra In Mr. Miki's "Symphony for Two Worlds," which combines a full Western orchestra with a 16·mem-bel' band playing Japanese instruments: here, Pro Musica Nipponia, founded by Mr. Mikin 1964.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakovwrote the book on orchestration •. but along· side the Japanese composer Minoru Miki In 'the New York Philharmonic concert at Avery Fisher Hall on Thursday evening, Rimsky seemed a piker. Kurt Masur led the orches-tra In Mr. Miki's "Symphony for Two Worlds," which combines a full Western orchestra with a 16·mem-bel' band playing Japanese instruments: here, Pro Musica Nipponia, founded by Mr. Mikin 1964.